5 - Dread-full thoughts on dread-emptiness

What is dread? Can we avoid it?

The Sun is getting lower and lower. Going away from us, into the Earth. They say that on Solstice-Day morning it will turn around and start coming back, that it will return from beneath the Earth. But what if it doesn’t? What if the Sun just keeps getting lower and lower until it’s gone away beneath the Earth forever and left us cold and dark and alone?

What is dread?

Dread is a dark fuzzy cloud in the human imagination that relentlessly works on visualizing the Very Worst Thing. Its cloudy gaze is aligned to point alongside the arrow of time: one cannot feel dread for what's past, only for what's to come.

Dread is to open up the aperture on tomorrow and to see, not sunlit vistas, but howling vacant waste peopled with gibbering bestial cannibal children. Our progeny, our descendants and our predators: they will eat us up and eat up our legacy too so we are completely and absolutely gone, bones and all. Maybe they are not children but machines, or empty-eyed puppets. No matter: they will still eat up our memory and leave nothing at all.

These are not necessarily simple-minded persons or happy persons or persons of stunted imaginations. But somehow they have retained a lifelong innocence, never knowing the dread some feel upon approaching the bedroom and facing that descent into the darkness of unknown worlds that may range from cartoonish absurdity to quaking horror. They are very lucky people. I wish I were one of them.

Thomas Ligotti, "My Work is Not Yet Done"

One thing we might notice about dread is that it practically doesn't exist anymore in academic discourse, having been subjected to a lexical downgrade in the last fifty or so years. It's been replaced by the lightweight abstract noun anxiety in most serious texts dealing with philosophy and psychology. Thus Kierkegaard's seminal philosophical essay The Concept of Dread is now issued under the title The Concept of Anxiety, presumably to correspond more closely with its Germanic cognate angst.

But if trauma is the Very Worst Thing situated in the past, and dread is the Very Worst Thing lurking somewhere in the future, then anxiety is simply a Very Bad Thing that's happening now. But it's not the Very Worst Thing, because if it was that you wouldn't be experiencing anxiety, but something else, a screaming nothing of terror, in fact. So anxiety is bad but survivable. But dread might not be survivable at all.

Meanwhile, as academic philosophers grapple with "anxiety", as if the deep-seated prospect of annihilation, suffering and death is somewhat akin to being embarrassed in a public setting or forgetting to match accessories with the correct outfit, critics of horror movies still remember what's what in their writeups: "dread" is still firmly in place as the descriptor for movies that sink the viewer into a state of bleak despair and unease.

Art-Dread

And not just horror movies: as an example, consider the Jeff Nichols film from 2011, Take Shelter starring Michael Shannon. We find that nearly all reviews of the film mention its overwhelming sense of dread. "A dread that seems quietly spreading in the land: that the good days are ending, and climate changes or other sinister forces will sweep away our safety," specified Roger Ebert. Other reviews: "a taut masterpiece of prescient dread", "an insidious dread throughout", "stunningly effective at establishing a sense of dread", and many others. It seems that whatever dread is, this film has plenty of it, and as it contains no supernatural spookies it might help us fix on what dread in its everyday sense actually is.

If we consider this film, and particularly what Shannon's character Curtis has come to dread, we find the following: global catastrophe, imagined as an extreme climate event, a storm to end all storms ("the storm is coming!" yells Curtis to his terrified rural community at a church social); his descent into the same madness that engulfed his mother; the death of his wife and daughter (conceivably by his own hand); unemployment, penury and with it the inability to receive any kind of medical care (a dread which is apparent to most ordinary people but not seen by Ebert or other comfortable cultural mavens who focus instead on climate change).

It is in all cases a fear of loss: loss of life, loss of loved ones, loss of position and status in society, loss of sanity, loss of protection, even loss of a planet which is amenable to life in any way. There is a loss of God which is understated but present: Curtis won't accompany his wife to church and has clearly lost his faith, if he ever had it. It points to a universal truth: what we have we can lose, at any time. The protection of the everyday can evaporate in a moment and leave us naked in the howling storm.

Michael Shannon's Curtis is important because as a blue-collar working stiff he reminds us that dread is not the preserve of effete scholars and anaemic philosophers, but a truly democratic curse open to embracing us all. Only the truly animal and unthinking are immune from its grasp in the dead of night.

I was going to start this essay with some fancy-ass analysis from such great thinkers as Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, but I've chosen instead to zoom in on the troubled care-worn face of Michael Shannon as a reminder that dread is not some academic exercise in precious self-valorization. It's the grip that takes hold of all of us, that tightening in the chest or the iron band around the forehead.

In fact it might be the true defining characteristic of human consciousness. First comes the mirror stage, the awareness that each individual is a bundle of thoughts and feelings wrapped in a meat packet which is vulnerable to oopsies, decrepitude and frailty. Then the dread stage, the mortal awareness that each and every one of us will die and that there's nothing to prevent it. Unless, that is, you're a techbro living in a nest made of quick-fixes and imagine that you can cheat death with cryo, cyber-uploading or some as-yet-untried combo thereof.

How can you live in the world in which we live and not lose your mind?... Everyone has a storm that's coming. Everyone has something on the horizon that doesn't seem like good news.

Michael Shannon on Take Shelter

Film may well do dread better than literature, because any kind of authorial voice tends to abstract the emotion away, to dramatise it or fancify it. Like whisky, dread is best taken neat. This is why the horror writers don't really evoke it, but rather provoke fear with their shadow terrors that are cousins to but not quite the thing itself.

Perhaps J.G. Ballard does it best in The Atrocity Exhibition, by absenting the authorial voice as much as possible and assembling repeated scenarios and fragments of our terminaol destiny. He leaves us with the Very Worst Thing abstracted out into a Max Ernst panorama of desolation, not crowded with monsters and bloodstains.

He listened to the helicopters. They seemed to alight on an invisible landing zone in the margins of his mind… All night he watched the sky, listening to the time-music of the quasars... Meanwhile the quasars burned dimly from the dark peaks of the universe, sections of his brain reborn in the island galaxies.

Ballard, The Atrocity Exhibition

There are two dimensions to dread: the interior, the personal and intimate - the silent whisper in the dead of night, the sense that things will very much not go your way - and the global, the urgent doomscrolling sense that something irreparable is happening, has already happened, and that the consequences of our inattention to that something will be so much worse than even the worst headlines hint at.

Out there and in here.

Dread and the time of dread

This is the area that contemporary strategic studies has recently become so fascinated with: the fear and dread crawling across the skin of nations, forcing the populace to take flight and flee across borders, unsettling and unbalancing other lands. The dry and academic talk of balance of power and international law has given way to the consideration of "mortality salience" as central to security. Nazi philosopher Carl Schmitt was the first, with his talk about actual bodily annihilation of real physical enemies as the secret essence of politics and law. Now the liberal "rules-based order" has died, the talk is all of uncovering buried bodies and staring at the moldering skulls of the killing fields or the famine plains.

Mortality disturbs the rationalist and modernist edifice of political sovereignty. Security was then postulated as one of many methods by which the knowledge of inevitable death – the limit point of rule – is effaced. In the era of modernity, security conceived of threat-objects and then acted against them with military/preventative tools to banish mortality and perform the perpetual nation state.

Charlotte Heath-Kelly, "The problem of dying while resilient" in Death and Security: Memory and Mortality at the Bombsite (2016)

I confess that I'm somewhat dread-impaired, incapable of succumbing to the chill grasp of its talons on my guts anymore. So I’m coasting on memories here. That's because of certain beliefs which make me unconvinced that anything we call ‘bad’ is actually any worse than anything we call ‘good’, that in the yowling vacancy of deep time, any reaction other than mute acceptance is absurd and futile.

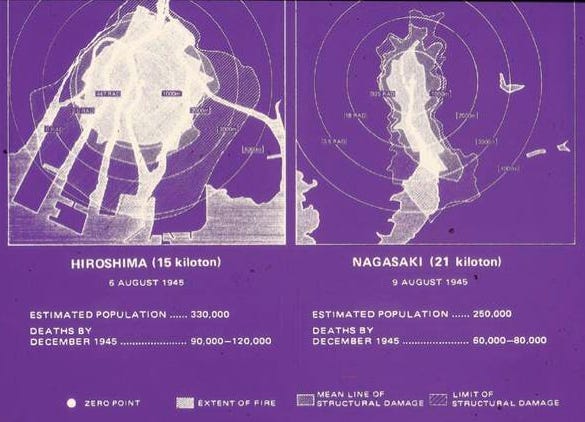

It's almost like faith, but it's a faith in the void itself to embrace us with its unknowing. It was actually birthed in the depth of the original Cold War, when it seemed the sirens could wail at any given moment. But it took some time to grow.

All explorations of dread, angst and unease on my part are therefore somewhat nostalgic, like stepping back into your old school and feeling the ghost of all the fears and insecurities that sat on your childish shoulders way back then.

The great big nothing of it all

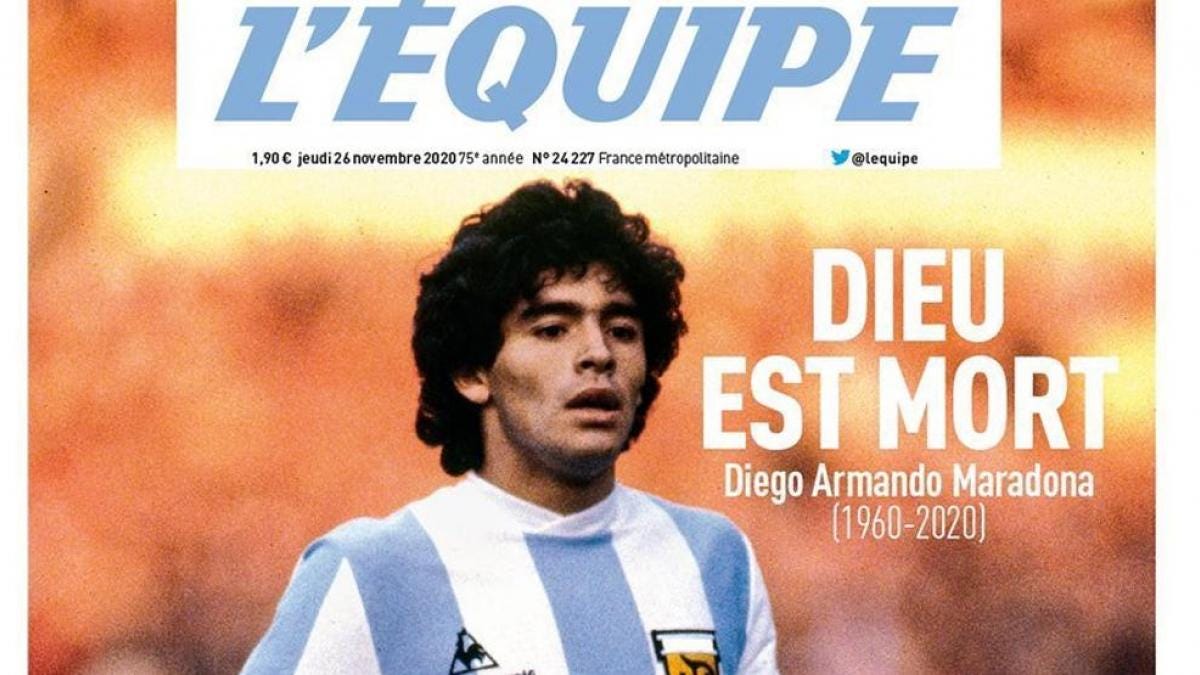

Are we not straying as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is not night continually closing in on us? Do we not need to light lanterns in the morning? Do we hear nothing as yet of the noise of the gravediggers who are burying God? Do we smell nothing as yet of the divine decomposition? Gods, too, decompose. God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.

Nietzsche, The Gay Science

At the end of Antonioni's film L'eclisse (The Eclipse) there's a sequence where the lovers Alain Delon and Monica Vitti are absent. The street corner where they used to meet before, planned to meet that night, is completely emptied of their presence and their significance. For a long time the afternoon passes and the evening comes, buses pull up, people read newspaper headlines about nuclear crisis, and pass on. The night comes and the lovers are still not there. They never come, in fact, and their failure to appear goes unexplained. They have been eclipsed by their own absence.

So there's the dreadful, the dread-full, that which is full of dread, and then there's the emptiness of absence, which counterintuitively might be more dreaded even than things that tear and crush, the howling chill wind of winter, and unending hunger pangs. When I was a kid they taught me about hell, torment everlasting - the priests always love the particulars of all the tortures, the drawn-out depictions of eternity spent in agony - but then came the nothingness. It was worse than all that active and busy hell for a time, but then it was better.

There’s no death in the conscious either. Epicurus, in trying to cure us of the fear of death, said: while we exist, death is not, and when death occurs, we do not exist. This truth, rather than reassuring us, instead is the cause of the long trouble, the unlocatable source of the shadow on our lives. The only thing that happens is the one thing we can’t experience.

Caleb Caudell, "Febreze Scented Corpse in a Tanning Booth"

Thus we take comfort in arts and entertainment, in drugs or sex or hobbies or just plain busywork. Anything to silence the dread and make it go away just for now. Maybe things will get better after the Solstice and the lifegiving Sun will return. Or maybe it won’t, and the Very Worst Thing will be upon me.

Before you go…

I’m hoping to get a discussion going on Dread in Literature and Art. References to art that foregrounds this, such as classic existentialist texts as well as horror and absurdist nihilism in books, comics and movies, are welcome.

If you’re interested in participating in such a chat, leave a comment or DM me and we’ll see if we can’t get a bookclubby-type chat going on this fascinating

And if you enjoyed this…

…there’s a thorough analysis of Take Shelter and its 2011 counterpart, Melancholia by Lars von Trier, in my film criticism Substack, Back to Back.

I must confess, I have just done a quick speed-read but will return to do a better job of it. I think Michael Shannon is an underrated actor that I've always enjoyed watching, and I have read Kierkegaard's Concept of Dread, which was difficult. I might be interested in further dreadful discussion. Thanks.

Just going to stick this post by Caleb here so that it's convenient when the time comes to round out the discussion

https://substack.com/@middleamericanliterature/note/c-81732561?utm_source=notes-share-action&r=2uhhe8