Occulted truths and obliterated tracks - Folk Horror as a genre (1 of 2)

Murph and Ivan J. Kirk get to grips with 'folk horror' in a two-part discussion

A.P. Murphy and Ivan J. Kirk, both authors of various types of fiction on Substack, some of it bordering on horror writing, have a shared passion for the horror genre, in both its classic British/American Gothic and more modern post-Poe forms.

Here they get together to discuss what makes ‘folk horror’ - is it really a thing? Or just a kind of dustbin to put horror texts and films that ‘aren’t really that scary’?

APM: I’ve always been a great fan of the classic Gothic tale, most especially as developed and practised by Edgar Allan Poe.

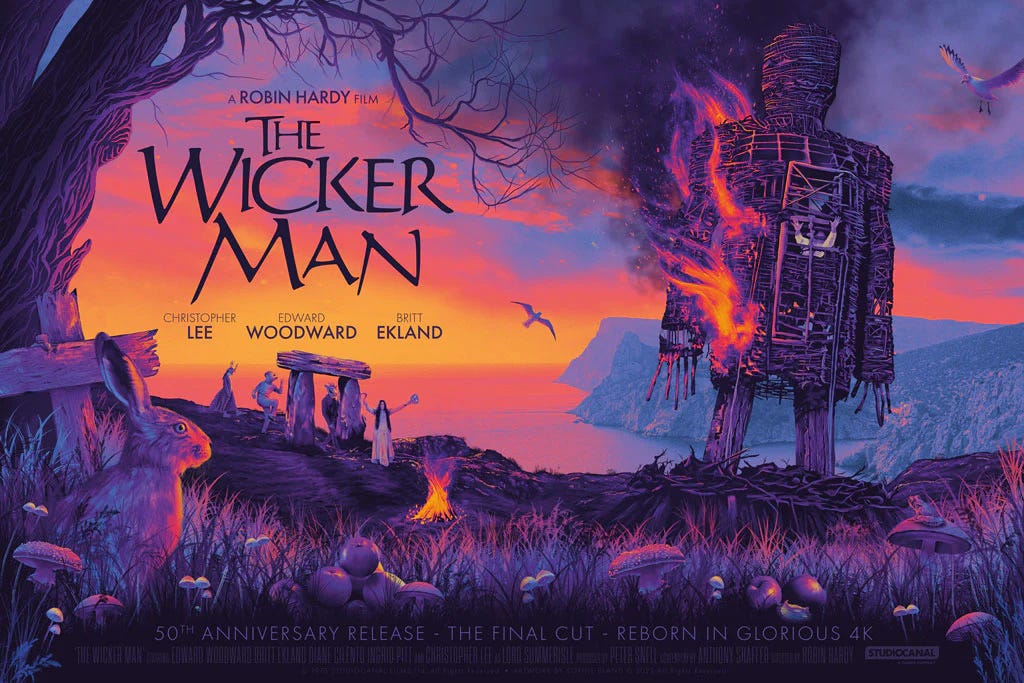

IJK: Likewise. I picked up Stephen King’s Night Shift at the right age, formed a convenient equivalence between horror and grown-up fiction, then followed the resulting obsession to Poe, M. R. James, Lovecraft, and, after watching The Wicker Man, anything I could find that halfway resembled it.

APM: For me the key theme and dynamic of the classic Gothic tale is the fragmentation of the unitary self under pressure from the anxiety of death itself, so the very mortality that drives the narrative as a threat is also an invitation to a kind of visionary ecstasy of despair. Poe simply knocks this narrative dynamic out of the park, so every threat of extinction is also an alluring temptation to self-annihilation, as in the scene in “The Imp of the Perverse” where the vertigo of a precipice is also a dreadful delight, a thrilling invitation to throw yourself off into oblivion.

We stand upon the brink of a precipice. We peer into the abyss. We grow sick and dizzy. Our first impulse is to shrink from the danger, and yet, unaccountably, we remain. By slow degrees our sickness, and dizziness, and horror, become merged in a cloud of unnameable feeling…it is but a thought, although one which chills the very marrow of our bones with the fierceness of the delight of its horror. It is merely the idea of what would be our sensations during the sweeping precipitancy of a fall from such a height. And this fall - this rushing annihilation - for the very reason that it involves that one most ghastly and loathsome of all the most ghastly and loathsome images of death and suffering which have ever presented themselves to our imagination - for this very cause do we now most impetuously desire it.

Poe, The Imp of the Perverse

It’s a fundamentally Romantic drive, I believe, but now under pressure in the era of heightened industrial capitalism. It’s a nostalgic yearning for the romantic and exotic that is also an escape and a release for Poe and for his readers. And also something much darker, a death instinct or as Freud would term it, Thanatos.

IJK: Not necessarily a death drive in Freud’s sense, I think, but a depolarised, disarticulated reality where no natural mandate can govern the narrator’s unnatural imp-ulse.

Chills the very marrow of our bones with the fierceness of the delight of its horror

APM: All this thunderous stuff will give way in the 20th century to the predominance, not of the high drama of self-annihilation and fragmentation of cohesive self-identity, but the quieter and creepier forces of the uncanny - later broken down into the weird and the eerie by Mark Fisher.

IJK: Right. For a long time I understood the Gothic tradition as a literature of depths - a place for realities too real for realism, the dark side of the bourgeois novel, etcetera. I was the sort of reader to whom the Freudian ‘uncanny’ stuff was attractive, though like Mark Fisher I was never particularly jazzed on castration anxiety.

APM: Very few people are all that jazzed about castration…

IJK: Then I read Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), and all of this exploded. Whatever vague innovationist ideas I had about the history of modern genres unraveled in the face of this barely-read classic, in which the horror, detective, fantasy, romance, family, and historical novels were all stitched up in one protean structure, more complex and ingenious than critics are still generally willing to acknowledge, which moreover had almost nothing to do with depths and everything to do with surfaces. The Gothic, I became convinced, was about perception, appearance, illusion, concealment, and revelation. Its subtending affect of horror-terror is enabled by the threat that no deep unifying ground exists to coordinate these perspectival surfaces into a providential order.

APM: This chimes with something I was working on quite some time ago. Way back in the Pleistocene era, I wrote my master’s thesis on Poe and his device of doubling - doubling both of characters, like the doppelganger of “William Wilson”, and doubling of the attitude to the genre he was working in, so he always seemed to write both a ‘serious’ Gothic tale and a weird comic-parodic take of every story concept that he came up with. The parodic ones are skimming the surface of the genre structures, trying to tease out the Gothic devices as rather goofy stuff, which in a sense they always are - ghosts and vampires are, apart from anything else, rather silly.

IJK: Yes - Gothics have this double structure, between what’s represented and the machinery of its representation, seriousness and parody. It’s not that they’re without depth, but that the depths they portentously gesture at can no longer be known, or assumed to exist. When we think of the major theme of British Gothic - the unwelcome appearance of the past in the present - we are ultimately faced with the threat that the enlightened certainties of modernity are no realer than the prejudices of the past. Edmund Burke, of all people, recognised this: writing contemporaneously with Udolpho and the French Revolution, he champions the patriotic British as “men of untaught feelings” who “instead of casting away all our old prejudices … cherish them because they are prejudices; and the longer they have lasted, and the more generally they have prevailed, the more we cherish them”. The best we can hope for in modernity is a useful fiction - but useful for what, and for whom?

Meanwhile Fisher’s categories “allow us to see the inside from the perspective of the outside”. This perspectival dimension interests me: to have our reality weirdened in the gaze of that which should not be, or to be folded by “the eerie power of landscape” into the “virtual infrastructure” of myth.

APM: A really great summation of the attraction of classic Gothic horror there, and a very pithy aphorism about the effect of horror fiction (which can of course be extended to surrealist/expressionist art of all kinds): “to have our reality weirdened in the gaze of that which should not be”, which I’ll surely be nicking in the near future. But to make the transition to Folk Horror: What’s our definition of Folk Horror (and can it really be said to be different from classic Gothic Horror)? And what texts (film, TV, or literature) best exemplify this new genre of the fantastic, if indeed it is new.

To have our reality weirdened in the gaze of that which should not be

Of course discussions of the Folk Horror as a genre, such as the very exhaustive but not particularly illuminating documentary Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched (2021), typically start with the Unholy Trinity of British horror movies Witchfinder General (1968), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) and above all The Wicker Man (1973).

IJK: This is what’s so interesting about the term. In the first place there’s an imbalance in the original canon: Witchfinder General and The Blood on Satan’s Claw are clearly similar (as period films about the same period, if nothing else), but The Wicker Man is unlike any other film ever made. Yet it becomes the lodestone for a genre designation that’s both hungry and picky about the entries it incorporates. Self-conscious folk horrors (Midsommar etc.) aren’t typical of this – what the Woodlands Dark filmmakers do, and what we’re doing now, is a rearticulation of ‘unclassifiable’ older texts as members of this depressingly empty genre, which for some reason we want to see filled. This was what folk horror devotees always had to do, before the 2010s resurgence, as fans of something that didn’t seem to reliably exist.

APM: But right now I’d like to take a different exemplar text, which is unusual since it erases the “folk” from the Folk Horror and leaves the natives as a complete absence which somehow inhabit the landscape itself as a nullity. There are no folkways here, just a mysterious something.This will give a very different idea of folk horror from one in which old pagan practices are revived or survive in a remote Scottish island.

I’m referring to Joan Lindsay’s novel Picnic at Hanging Rock (1967), and most particularly the Peter Weir movie adaptation from 1975. I’m aware of an Aussie TV miniseries from recent times, though I haven’t seen it, and can’t imagine what it could possibly add to the film by being extended to a runtime of several hours.

My more complete review of the movie on Letterboxd, which gives it a perfect 5-star rating, explains the background a little bit more, and also offers what I think is a fair tentative working definition of folk horror:”a type of horror that is often soft on the horror and heavier on the folk, meaning a primordial sense of connection with the transcendent through magic and ritual connected with nature.” This is a definition we can beat around a little and see how it responds to stress.

There’s no folk or folk ritual in this film, which has a great deal to do with the colonial background of Australia itself, or more properly the British Empire, which did its best to exterminate the folk that inhabited the landscape. The residual magic is contained exclusively in the landscape, which is empty of what should be there, or as Fisher describes it in The Weird and The Eerie (2016) the, uh… eerie.

The first shots of the film contrast the Hanging Rock itself, empty and hovering over the landscape in haze with the girls’ boarding school, an Anglicised place of “civilization”. But there’s nobody in either place at the start. Both are eerie and void of life.

At the magical site which is the Hanging Rock, all the folk have gone away and in their place is mystery. Fisher says of it:

Picnic at Hanging Rock is practically a textbook example of an eerie novel - it includes disappearances, amnesia, a geological anomaly, an intensely atmospheric terrain - but also because Lindsay’s rendition of the eerie has a positivity, a languorous and delirious allure, that is absent or suppressed in so many other eerie texts.

Mark Fisher, “The Eerieness Remains” in The Weird and the Eerie (2016)

What’s your feeling about this story? Is it even right to consider it folk horror? And how about my working definition? Can it hold up, or is there something lacking?

IJK: I’m completely with you on Picnic at Hanging Rock actually being folk horror, but not entirely confident of why. To your point about the colonial background, eerie emptiness is a signature of Australian Gothic, which is a busy tradition (seekers of classic, Victorian-period horror could do worse than checking out people like Henry Lawson, Barbara Baynton…). There’s a passage from Marcus Clarke, one of our mid-Victorian guys, which I’ll quote as selectively as I can:

In historic Europe, where every rood of ground is hallowed in legend and in song, the least imaginative can find food for sad and sweet reflection [...] But this our native or adopted land has no past, no story. No poet speaks to us. [...] In the Australian forests no leaves fall. The savage winds shout among the rock clefts. From the melancholy gums strips of white bark hang and rustle. The very animal life of these frowning hills is either grotesque or ghostly. [...] From a corner of the silent forest rises a dismal chant, and around a fire dance natives painted like skeletons. All is fear-inspiring and gloomy.

This is typical of the tradition behind Picnic at Hanging Rock, referenced by it in the Victorian setting: a world empty of ancestral meaning, of falling leaves, of the basic geographical facts that make the nouns in British poetry make sense. But also too full: the wind itself is strangely agential, there are “[w]hite cockatoos … shrieking like evil souls”, and an Indigenous presence which hints at alternative traditions of “legend and … song” that people like Clarke want nothing to do with, except as material for ghost tales. Picnic’s boarding school “attempt[s] to simulate a small part of Victorian England in conditions that could hardly be more different from Britain” (Fisher), making this eerie failure of meaning the novel’s background radiation.

In Chapter 3, the girls first apprehend Hanging Rock as a Romantic cliche: “The immediate impact of its soaring peaks induced a silence so impregnated with its powerful presence that even Edith was struck dumb”. In the next paragraph, the tense changes, along with the focus:

they walk silently towards the lower slopes, in single file, each locked in the private world of her own perceptions, unconscious of the strains and tensions of the molten mass that hold it anchored to the groaning earth: of the creakings and shuddering, the wandering airs and currents known only to the wise little bats, hanging upside down in its clammy caves. None of them see or hear the snake dragging its copper coils over the stones ahead. Nor the panic exodus of spiders, grubs, and woodlice from rotting leaves and bark. There are no tracks on this part of the Rock. Or if there ever have been tracks, they are long since obliterated.

The film renders this bit with a cutaway nature documentary montage – an area where I don’t think it quite nails the texture of the book.

Lindsay lapses into present tense a few more times: in Chapter 10, when the narrator steps in to warn us of unseen workings (“The reader taking a bird’s eye view of events since the picnic will have noted how various individuals on its outer circumference have somehow become involved in the spreading pattern”).

Present tense is also present in the ‘missing’ final chapter, cut from the manuscript before publication in the 60s, and published separately in 1987: “It is happening now. As it has been happening ever since Edith Horton ran stumbling and screaming towards the plain. As it will go on happening until the end of time”.

So when Fisher writes of Picnic that “the inclusion of Chapter 18 pushes the novel into some space between the weird and the eerie”, I don’t think he’s being responsible to his categories. Lindsay is almost on-the-nose about when one mood gives way to the other: the eerie belongs to limited perspective in past tense, as when Edith watches her schoolmates “sliding over the stones on their bare feet as if they were on a drawing-room carpet”, unable to perceive the force that compels them; when it’s time for the reader to see further even than creepy Marion and glimpse past the categories that regulate civilised perception, we cross a threshold marked by present-tense omniscience, and must now reconsider how reality works.

I suspect this is the dimension that makes ‘folk horror’ feel appropriate for Picnic and not for the older Australian Gothics. Less perhaps that “folk” is equivalent to ritually-accessed transcendent nature (per your definition) than that a conflict is staged between myopic modernity and a weird nature that’s absolutely disjunctive with civilisation.

Yvonne Rousseau, the prolific interpreter of Picnic, concluded that the missing girls disappeared from the mundane world to become part of the Dreaming. I won’t pretend to Indigenous knowledge and try to explain Dreaming, but fortunately nor does Rousseau: she explains her interpretation through the lens of European occultism, with the country possessing an “astral body” and “astral consciousness” beyond space and time, into which the missing girls lose their physical extension and become archetypes, forever ‘repeating’ their disappearance in an eternal present tense.

This syncretism is a clue to something, I think. Joan Lindsay’s friends have said she was a “mystic” who “was very interested in Arthur Conan Doyle and his belief in and theories about Spiritualism, nature and the existence of spirits”. So were Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood; Margaret Murray is also in that conversation, and James Frazer by extension. Perhaps when we detect folk horror in something, we’re partly detecting the influence of Victorian Spiritualism – the scary side of a worldview that scours the history of religion for occulted truths.

NEXT TIME

The terror twosome delve into more canonical folk horror, and find infinite loops of myth and destiny in a lonely Welsh valley…

SUGGESTED READING

Marcus Clarke, “Preface”. Poems, Adam Lindsay Gordon (1893)

Robert Edgar & Wayne Johnson (eds) - The Routledge Companion to Folk Horror (2023)

Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie (2016)

David Punter, The Literature of Terror A History of Gothic Fictions from 1765 to the Present Day, Volume 1: The Gothic Tradition & Volume 2: The Modern Day (1996)

PRIMARY TEXTS

Joan Lindsay, Picnic at Hanging Rock (1967)

Edgar Allan Poe, “The Imp of the Perverse” (1845) in Works Volume 2

Ann Radcliffe, The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794)

Brilliant! Enjoyed this discussion very much. Ever think of starting a podcast?

I've got homework now! Awesome discussion. Can't wait for part two! But I'll ask that you no longer disparage Horror Horror or Ghosts and Vampires going forward. ;)