1 - Cruel Optimism

When the cruellest thing you can do to yourself is wish the wrong wish

A relation of cruel optimism exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing. It might involve food, or a kind of love; it might be a fantasy of the good life, or a political project. It might rest on something simpler, too, like a new habit that promises to induce in you an improved way of being. These kinds of optimistic relation are not inherently cruel. They become cruel only when the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially.

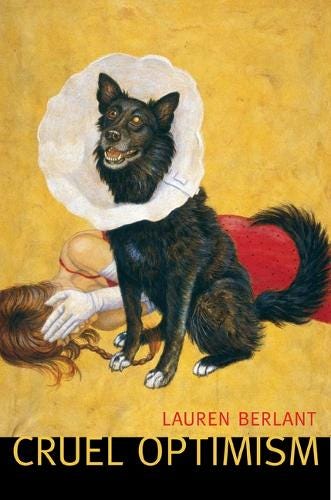

Cruel Optimism by Lauren Berlant (2011)

When Lauren Berlant penned this book in 2010-ish, the wounds of the Great 2008 Steal were still fresh. It seemed unthinkable that we'd just done it, but we had.

We’d let the finance guys squander all our money, allowed them to start weeping in public that the system was in Mayday! mode, then we gave them what we couldn't afford and watched them walk away without a single one of them facing a penalty for the unprecedentedly enormous criminal fraud they'd perpetrated. 1

The post-war dream was over and even us mugs were beginning to notice:

The fantasies that are fraying include, particularly, upward mobility, job security, political and social equality, and lively, durable intimacy. The set of dissolving assurances also includes meritocracy, the sense that liberal-capitalist society will reliably provide opportunities for individuals to carve out relations of reciprocity that seem fair and that foster life as a project of adding up to something and constructing cushions for enjoyment.

So far, so conventional insight. Stark and unpleasant to behold, like an election candidate seen in full sunlight, but hardly new or unexpected analysis. What Berlant brings to the table is the awareness that though we understand on the conscious level that we're being lied to, that our entire political and economic life is built on a scam, we just cannot cope with this understanding on a subconscious level where all our unacknowledged fears and desires reside. So nothing changes.

Laurent Berlant, author of Cruel Optimism

In her own words, she "politicizes Freud’s observation that 'people never willingly abandon a libidinal position, not even, indeed, when a substitute is already beckoning to them.'" In other words, our Freudian id just won't let go of capitalism even if our Freudian ego is telling us it's a bust (to simplify things quite crudely - what Freud's really saying is that our desires get stuck in a rut, and Berlant identifies that rut as our desire-based economy).

That interlocks quite closely with Mark Fisher's much better-known concept of Capitalist Realism, that after many generations of classical capitalism and at least two generations of the tumorous outgrowth that is neoliberal final-stage capitalism, any other type of society is simply inconceivable for us.

Which is why utopias today are imagined as neoliberalism now burst out of its supposed chains as anarcho-capitalism, and other forms of Silicon Valley High Fantasy. But we'll leave Fisher's Capitalst Realism and Malcolm Harris's Palo Alto of the Soul for other installments of this series. Right now, let's get back to Berlant.

What is optimism? It's believing things can get better, of course. Nothing wrong with that; at worst you might consider it a necessary fiction to get us through the day ahead. But what if it is worse? What if it's the very optimism that is preventing things from getting better, a paradoxical knot or tangle that only the sharpest blade could cut through. Let's break it down:

1) Optimism as attachment. What we desire becomes something that we attach to ourselves. It is 'our' desire, and even if unsatisfied it's still our own.

All attachments are optimistic. When we talk about an object of desire, we are really talking about a cluster of promises we want someone or something to make to us and make possible for us. This cluster of promises could seem embedded in a person, a thing, an institution, a text, a norm, a bunch of cells, smells, a good idea—whatever.

This attachment, this want, becomes part of our selves, like things sticking to you by velcro strips. Once attached, they are part of you unless stripped away, a painful process - so very much unlike velcro really, unless the velcro is your own skin. Let's say a sticking plaster, a band-aid made of need. Now we're getting there.

2) Cruelty is in how the optimism ends up destroying your hope because you can't live without it. First the general description, then some concrete examples:

“Cruel optimism” [is] a relation of attachment to compromised conditions of possibility whose realization is discovered either to be impossible, sheer fantasy, or too possible, and toxic. What’s cruel about these attachments, and not merely inconvenient or tragic, is that the subjects who have x in their lives might not well endure the loss of their object/scene of desire, even though its presence threatens their well-being, because whatever the content of the attachment is, the continuity of its form provides something of the continuity of the subject’s sense of what it means to keep on living on and to look forward to being in the world.

Can't live with it, can't live without it. A double bind, or fucked-if-you-do, fucked-if-you-don't type situation. What are we actually talking about in terms that relate to our day-to-day experience?

"This might point to something as banal as a scouring love, but it also opens out to obsessive appetites, working for a living, patriotism, all kinds of things." Basically anything that isn't the satisfaction of the most basic needs - and it could surely be argued that 'working for a living' is one of those necessaries - could become, could but not necessarily must, could become a cruelly optimistic desire or attachment.

Cruel optimism as your day-to-day life

Berlant gets into some Marxist analysis of the Fetishization of the Commodity and Exchange Value before bringing it all back down to earth with "Exchange Value", Charles Johnson’s gritty realist-surrealist tale of two black brothers in the South Side of Chicago in the 1970s. 2

Charles Johnson, from 1974 when the story is set; it was written some years later in 1981

The interplay between this tremendous story of ghetto life, a kind of Blaxploitation Crime and Punishment, Marx's theory of value and the commodity, Berlant's analysis in terms of fantasy and realism, and the actualities of actual life, living an actual life beyond all of these abstractions and narratives, is the highlight of the book, in my opinion.

The fantasy that is one brother's attachment to comic-book stories of Batman and Superman, the DCEU as we call it today, becomes equivalent to a rich hoarder's fantasy attachment to all the things, from cash to trinkets to sheer junk, that one can accumulate. The 'real value', or Marx's use-value, of all these things, is lost to sight in this swirl of fetishized thinginess. And by doing so some sight is restored.

Once your eyes are open to cruel optimism, you see it everywhere, in your life and the life of others, as a pall of wasteful hope hanging over so many thoughts and deeds. It's most obvious in those toxic dependent relationships or those substance dependencies that cost so much pain to overcome. But your 'Cruel and Unusual Nourishment', the food that doesn't actually keep you healthy but keeps you unhealthy because you've been hooked onto it? Is that an optimistic attachment? Your job? It seems that during the 'Great Quit' of the post-pandemic lots of people decided that their job wasn't doing it for them, though it's far too early to tell what exactly went on there.

Ploughing through Berlant's rich book, full of philosophical theory, psychoanalysis, embedded stories from literature and film, from TV shows that start as sitcoms and end as 'situation tragedies', there's a lot to chew on. A lot that you might happily swallow and a lot you might spit out again because it tastes bad. A lot. I'm still moving through it, and I have to say that in the 14 years since it came out it has only become more relevant.

You can't judge a book by its cover, so they say, but you can begin to get a sense of this one by the unforgettable image on the front.

That's because the cover is actually part of the text, so in this case the superficiality of fixating on the package’s wrapping is justified by some profound insight. I'll let Hua Hsu of The New Yorker take over here:

There’s a stirring moment, at the end of Cruel Optimism, when Berlant writes about the book’s cover image, a painting that depicts the artist and disability activist Riva Lehrer lying beside her dog, Zora. Lehrer seems to float behind Zora, her hand covering her face. Zora is blind in one eye and wears a cone around her neck. They are, by conventional standards, limited and vulnerable beings. But, to Berlant, they are a “team.” They “seem at peace with each other’s bodily being, and seem to have given each other what they came for: companionship, reciprocity, care, protection.” In the absence of real stability—the state of affairs that we must come to terms with—there is still the possibility of true solidarity, the experience of “having adventures and being in the impasse together, waiting for the other shoe to drop, and also, allowing for some healing and resting, waiting for it not to drop.”

So it's not all doom and gloom, though there is a fair amount of that going on too. But in the spirit of healing therapy - where the first stage in recovering from your trauma is acknowledging that it exists - although this book could be the pill that is hardest to swallow, it may be the most truly, actually, optimistic thing of all.

Painting by Riva Lehrer

NOTES

I'm stowing all the 'allegedlys' for two reasons: first, it's an ungraceful word to be peppering all over your text, and second, there ain't nothing alleged about it - it was an honest-to-God megascam in which the money-engineers bundled up high-risk product in complex packages and floated these toxic turds of mortal danger without any possible way of checking just how much shit they were immersing us in.

Charles Johnson's story is published in American Gothic Tales (1996). Edited by Joyce Carol Oates. A must read.

Does the book only tackle economics, or does it treat all aspects of life? Interest piqued.

Lol. I like your throwing shade at patriotism. Double-lol! How many things do we strive for, unknowingly to our own detriment? So interesting. You just cracked my head wide open. This Cruel Optimism peppers everything we do.